An artist’s impression showing the increasing effect of ram-pressure stripping in removing gas from galaxies, sending them to an early death

Image Credit: ICRAR, NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

Large galaxies are known to strip the gas that occupies the space between the stars of smaller satellite galaxies.

Large galaxies are known to strip the gas that occupies the space between the stars of smaller satellite galaxies.

In research published today, astronomers have discovered that these small satellite galaxies also contain less ‘molecular’ gas at their centres.

Molecular gas is found in giant clouds in the centres of galaxies and is the building material for new stars. Large galaxies are therefore stealing the material that their smaller counterparts need to form new stars.

Lead author Dr Adam Stevens is an astrophysicist based at UWA working for the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) and affiliated to the ARC Centre of Excellence in All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D).

Dr Stevens said the study provides new systematic evidence that small galaxies everywhere lose some of their molecular gas when they get close to a larger galaxy and its surrounding hot gas halo.

“Gas is the lifeblood of a galaxy,” he said.

“Continuing to acquire gas is how galaxies grow and form stars. Without it, galaxies stagnate.

“We’ve known for a long time that big galaxies strip ‘atomic’ gas from the outskirts of small galaxies.

“But, until now, it hadn’t been tested with molecular gas in the same detail.”

ICRAR-UWA astronomer Associate Professor Barbara Catinella said galaxies don’t typically live in isolation.

“Most galaxies have friends,” she says.

“And when a galaxy moves through the hot intergalactic medium or galaxy halo, some of the cold gas in the galaxy is stripped away.

“This fast-acting process is known as ram pressure stripping.”

The research was a global collaboration involving scientists from the University of Maryland, Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, University of Heidelberg, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, University of Bologna and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Molecular gas is very difficult to detect directly.

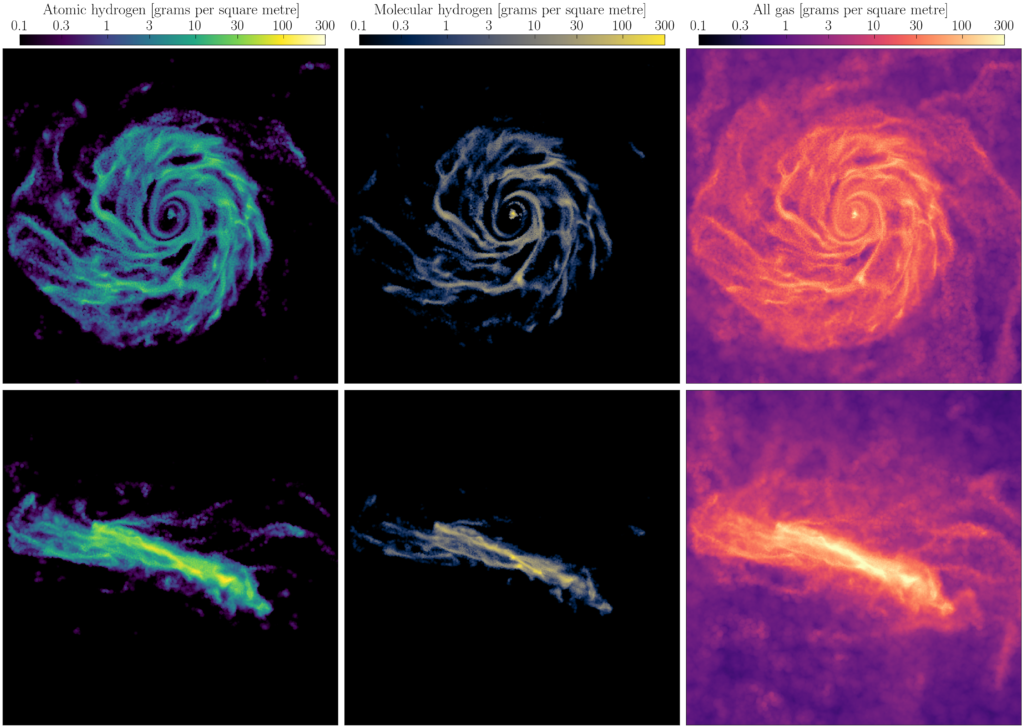

The research team took a state-of-the-art cosmological simulation and made direct predictions for the amount of atomic and molecular gas that should be observed by specific surveys on the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico and the IRAM 30-meter telescope in Spain.

A massive, simulated galaxy showing its first signs of gas stripping (Credit: Adam Stevens/ICRAR)

They then took the actual observations from the telescopes and compared them to their original predictions.

The two were remarkably close.

Associate Professor Catinella, who led the Arecibo survey of atomic gas, says the IRAM 30-meter telescope observed the molecular gas in more than 500 galaxies.

“These are the deepest observations and largest sample of atomic and molecular gas in the local Universe,” she says.

“That’s why it was the best sample to do this analysis.”

The team’s finding fits with previous evidence that suggests satellite galaxies have lower star formation rates.

Dr Stevens said stripped gas initially goes into the space around the larger galaxy.

“That may end up eventually raining down onto the bigger galaxy, or it might end up just staying out in its surroundings,” he said.

But in most cases, the little galaxy is doomed to merge with the larger one anyway.

“Often they only survive for one to two billion years and then they’ll end up merging with the central one,” Dr Stevens said.

“So it affects how much gas they’ve got by the time they merge, which then will affect the evolution of the big system as well.

“Once galaxies get big enough, they start to rely on getting more matter from the cannibalism of smaller galaxies.”