This month’s Monthly Media comes from Associate Professor Duane Hamacher, from our University of Melbourne node, on an upcoming paper that looks into the commonality of constellations across cultures, using a simple computational model to predict the most likely asterisms (grouping of stars) to be included in the local traditions.

Duane and his colleagues set out to determine if the groupings of bright stars are a major predictor of asterisms (perceptual groupings), or if cultures are more likely to project their most important figures onto the sky, capturing whatever stars happen to be in the area (cultural groupings). Both play their part, but to what extent?

Previously there were only a handful of asterisms attributed to perceptual groupings, which included Orion’s Belt, the Pleiades, the Big Dipper (Northern Hemisphere only) and the Southern Cross (Southern Hemisphere only).

Through this research, they have discovered that the primary predictor of a culture’s asterisms is perceptual grouping, as many bright and apparently close groups of stars in our skies have been grouped together by many diverse cultures.

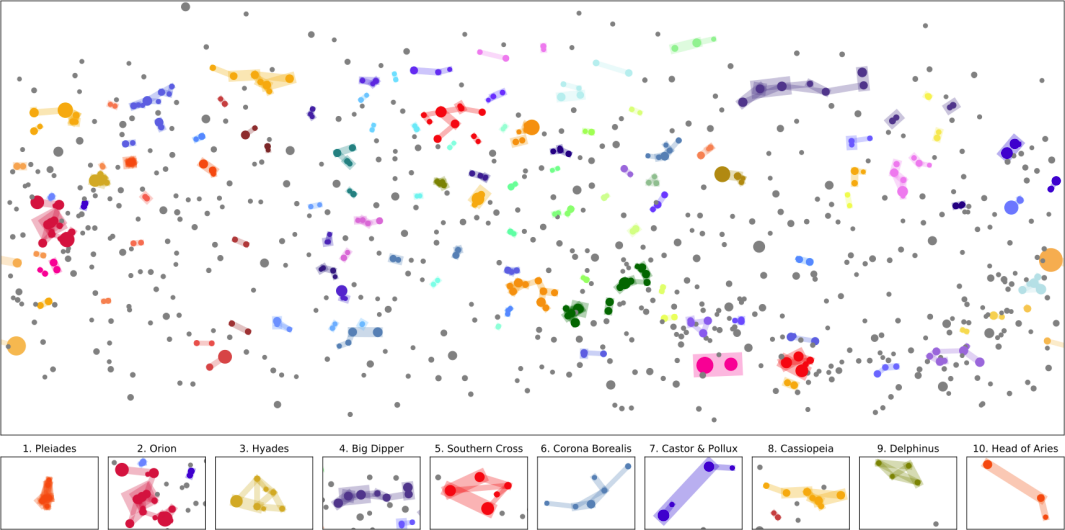

The two figures compare the most commonly seen asterisms within the cultures considered in the study to the predictions of the computational model based on perceptual grouping. This shows there is a strong relationship between the brightness and apparent distances between stars on the sky, and a culture’s tendency to group them together as part of their astronomical traditions and stories.

Upper panels: 10 of the most common asterisms across the 27 cultures included in the study. Lower panel: Consensus of asterisms of the 27 cultures included in the study, where the edges shown appear in at least 4 cultures. Edge width thickness is determined by the number of cultures they appear in. Apparent star brightness is indicated as the size of the dots, with only magnitudes brighter than 4.5 shown. Numbers greater than 10 identify the asterisms of: Southern Pointers (11), shaft of Aquila (12), Little Dipper (13), head of Scorpius (14), stinger of Scorpius (15), sickle in Leo (16), Corvus (17), Northern Cross (18), Lyra (19), Square of Pegasus (20), Corona Australis (21), head of Draco (22) and the teapot in Sagittarius (23).

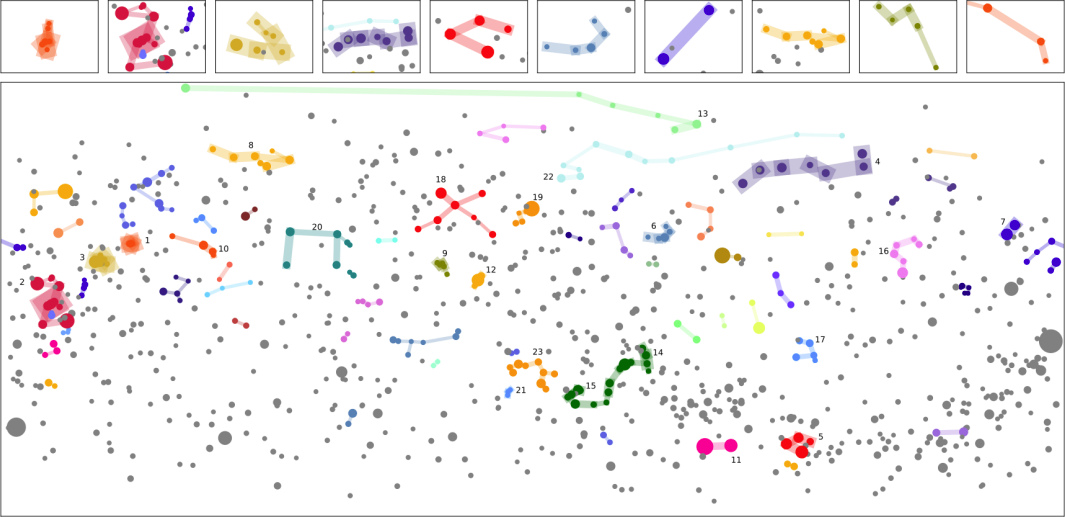

Upper panel: Asterisms according to the computational model such that only the strongest 320 edges are shown (n=320). Edge widths are proportional to the strengths assigned by the model. Apparent star brightness is indicated as the size of the dots, with only magnitudes brighter than 4.5 shown. Lower panel: The models findings for the same 10 most common asterisms across the 27 cultures shown in figure 1.

The model also showed that of the 27 cultures included, the Chinese system is the least like the others, with many small asterisms that do not appear elsewhere. As such, this model can be further used to understand historical relationships between cultures, and what cultural groups have most influenced each other’s systems.

There are other interesting similarities between astronomical systems that present potential future work, such as the similarities between the stories themselves that describe these recurring asterisms. But that’s a story for a future Monthly Media.

Leave A Comment