Sky survey provides clues to how they change over time.

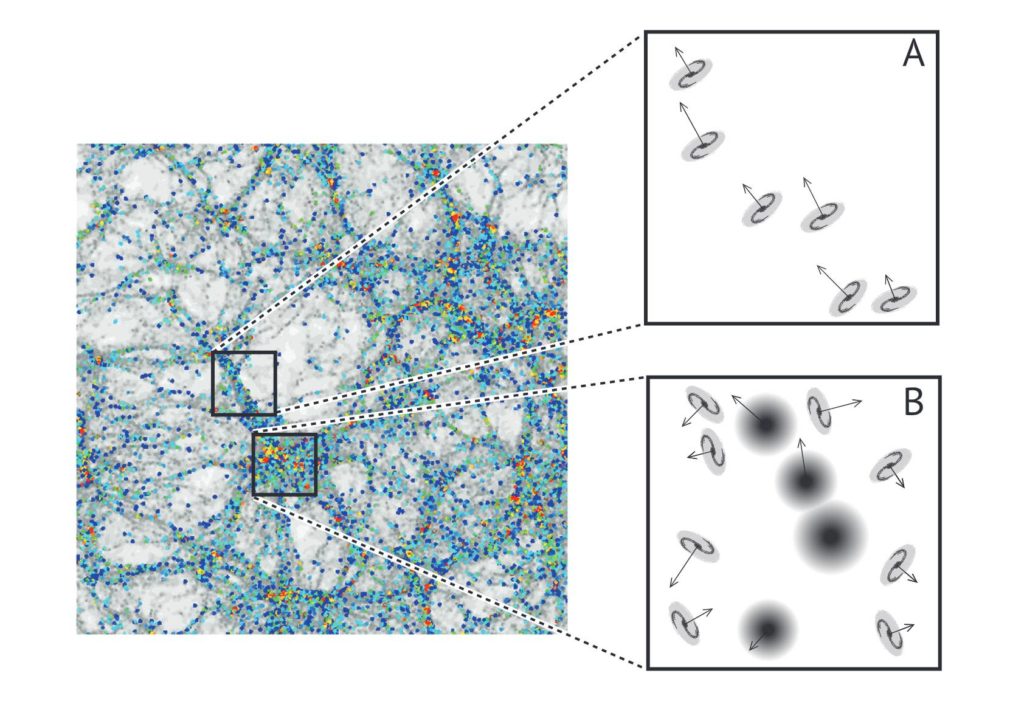

The direction in which a galaxy spins depends on its mass, researchers have found. A team of astrophysicists analysed 1418 galaxies and found that small ones are likely to spin on a different axis to large ones. The rotation was measured in relation to each galaxy’s closest “cosmic filament” – the largest structures in the universe.

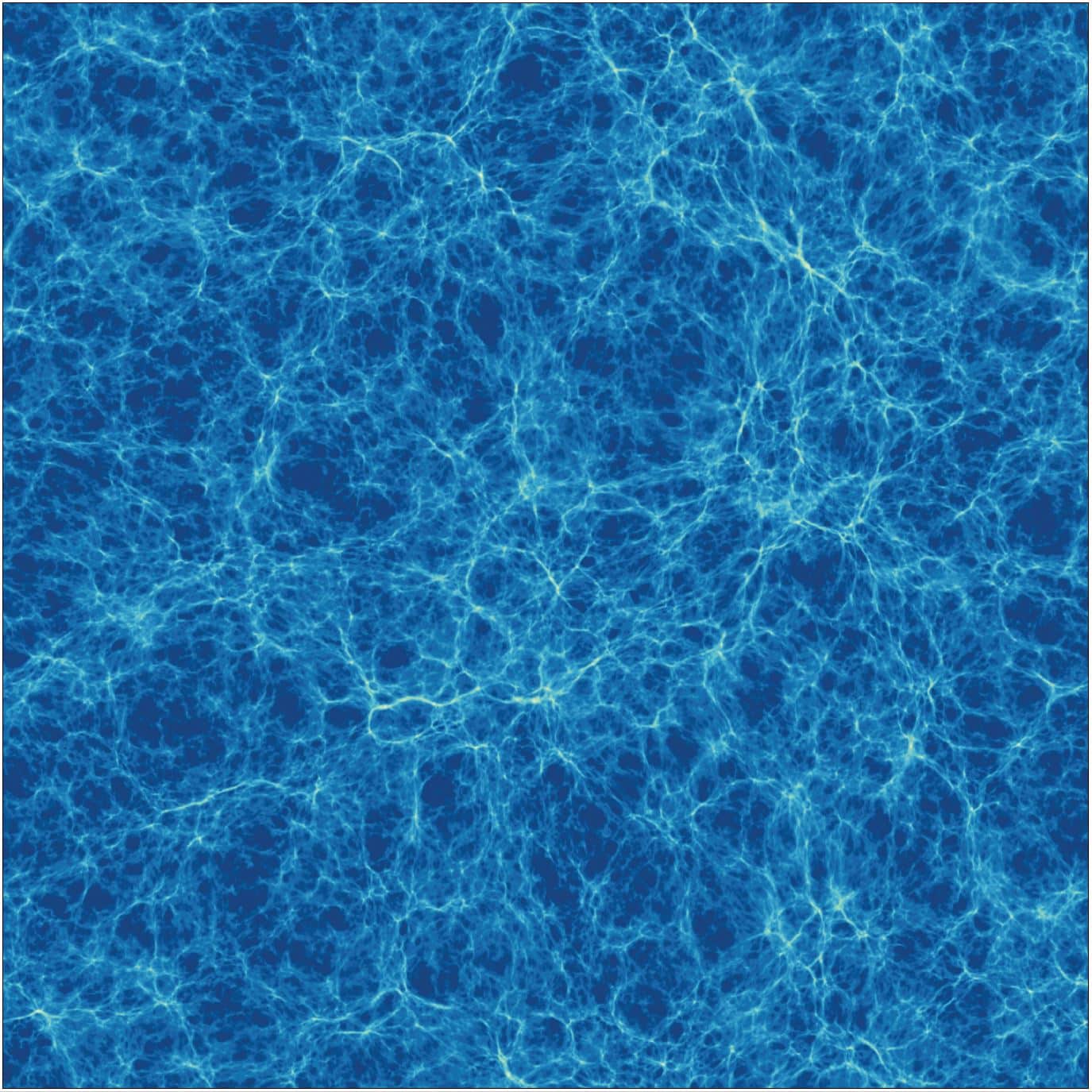

Filaments are massive thread-like formations, comprising huge amounts of matter – including galaxies, gas and, modelling implies, dark matter. They can be 500 million light years long but just 20 million light years wide. At their largest scale, the filaments divide the universe into a vast gravitationally linked lattice interspersed with enormous dark matter voids.

A simulation showing a section of the Universe at its broadest scale. A web of cosmic filaments forms a lattice of matter, enclosing vast voids. Credit: Tiamat simulation, Greg Poole

“It’s worth noticing that the spine of cosmic filaments is pretty much the highway of galactic migration, with many galaxies encountering and merging along the way,” says lead researcher Charlotte Welker, an ASTRO 3D researcher working initially at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) and now at McMaster University in Canada.

The filaments are why the universe looks a little like a honeycomb, or a cosmic Aero chocolate bar.

Using data gathered by an instrument called the Sydney-AAO Multi-object Integral-field spectrograph (SAMI) at Australia’s Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT), Dr Welker, second author and ASTRO 3D principal investigator Professor Joss Bland-Hawthorn from the University of Sydney, and colleagues from Australia, the US, France and Korea studied each of the target galaxies and measured its spin in relation to its nearest filament.

They found that smaller ones tended to rotate in direct alignment to the filaments, while larger ones turned at right angles. The alignment changes from the first to the second as galaxies, drawn by gravity towards the spine of a filament, collide and merge with others, thus gaining mass.

It is a phenomenon that Dr Welker likens to roller-skating in the company of a friend.

“The flip can be sudden,” she says. “Merging with another galaxy can be all it takes.

“Imagine you are skating after a friend and catching up. If you grab your friend’s hand while you are still moving faster, you will both start rotating on a vertical axis – a spin perpendicular to your horizontal path.

“However, if a small cat – a much lighter bit of matter – runs after your friend and jumps on her she probably won’t start spinning. It would take a lot of cats leaping on her at once to change her rotation.”

Co-author Scott Croom from the University of Sydney, also an ASTRO 3D principal investigator, says the result offers insight into the deep structure of the Universe.

“Virtually all galaxies rotate, and this rotation is fundamental to how galaxies form,” he says.

“For example, most galaxies are in flat rotating disks, like our Milky Way. Our result is helping us to understand how that galactic rotation builds up across cosmic time.”

He adds that a new instrument, called Hector, set to be installed at the Anglo Australian Telescope next year, will enable a significant expansion of research in the field.

“Hector will be able to carry out surveys five times larger than SAMI,” he says. “With this we will be able to dig into the details of this spin alignment to better understand the physics behind it.”

The Milky Way, by the way, has a spin well aligned with its nearest cosmic filament, but belongs to a class of intermediate size galaxies that, overall, show no clear tendency towards parallel or perpendicular spins.

“It’s like saying that there is no preference for tea or coffee among a group of people,” says Dr Welker. “Individuals may still prefer either tea or coffee, but overall there is no general tendency towards coffee in the group.”

The research has early access availability in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRS), and is also available in full on the preprint site arxiv.

ASTRO3D is the ARC Centre of Excellence for Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions.

Media contacts:

Dr Charlotte Welker: 289 639 1918, time zone is GMT-5; please ask to speak to Dr Welker

Professor Scott Croom: +61 450 103 695, time zone is GMT+11

Professor Joss Bland-Hawthorn: +61 406 973 133, time zone is GMT+11

Professor Lisa Kewley, ASTRO 3D director: +61451 045 968, time zone is GMT+11

Further assistance:

Andrew Masterson: andrew@scienceinpublic.com.au; +61488 777 179, time zone is GMT+11

Funding:

The research was funded Australian Research Council grants FF0776384 and LE130100198, an ARC Laureate Fellowship, and ARC Future Fellowship, the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO), the Flagship Allocation Scheme of the NCI National Facility at the ANU, and the National Science Foundation.

The paper:

The SAMI Galaxy Survey: First detection of a transition in spin orientation with respect to cosmic filaments in the stellar kinematics of galaxies.

- C. Welker 1,2,4,5;

- J. Bland-Hawthorn3,4;

- J. Van de Sande3,4;

- C. Lagos1,4;

- P. Elahi1,4;

- D. Obreschkow1,4;

- J. Bryant3,4;

- C. Pichon5,12;

- L. Cortese2,4;

- S. N. Richards6;

- S. M. Croom3,4;

- M. Goodwin7;

- J. S. Lawrence8;

- S. Sweet9,4;

- A. Lopez-Sanchez8;

- A. Medling10,11;

- M. S. Owers13;

- Y. Dubois5;

- J. Devriendt14,15

Department of Physics and Astronomy, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- ICRAR, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Perth, 6009, Western Australia

- Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, A28, The University of Sydney, NSW, 2006, Australia

- ARC Centre of Excellence for Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D)

- CNRS and UPMC Univ. Paris 06, UMR 7095, Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 98 bis Boulevard Arago, F-75014 Paris, France

- SOFIA Science Center, USRA, NASA Ames Research Center, Building N232, MS 232-12, P.O. Box 1, Moffett Field, CA 94035-0001, USA

- Australian Astronomical Observatory, 105 Delhi Rd, North Ryde, NSW 2113, Australia

- Australian Astronomical Optics, Macquarie, Macquarie University, NSW 2109, Australia

- Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, PO Box 218, Hawthorn, VIC 3122

- Ritter Astrophysical Research Center University of Toledo Toledo, OH 43606, USA

- Research School for Astronomy and Astrophysics Australian National University Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia

- Korea Institute of Advanced Studies (KIAS) 85 Hoegiro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, 02455, Republic of Korea

- Department of Physics and Astronomy, Macquarie University, NSW 2109, Australia

- Sub-department of Astrophysics, University of Oxford, Keble Road, Oxford, OX1 3RH, United Kingdom

- Observatoire de Lyon, UMR 5574, 9 avenue Charles Andre, Saint Genis Laval 69561, France

MNRAS version:

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2019MNRAS.tmp.2470W/abstract

Arxiv version: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.12371.pdf

Additional photographs: